Le présent article a été rédigé par Jonathan Goldberg, que je remercie. Une traduction en français sera publiée ultérieurement.

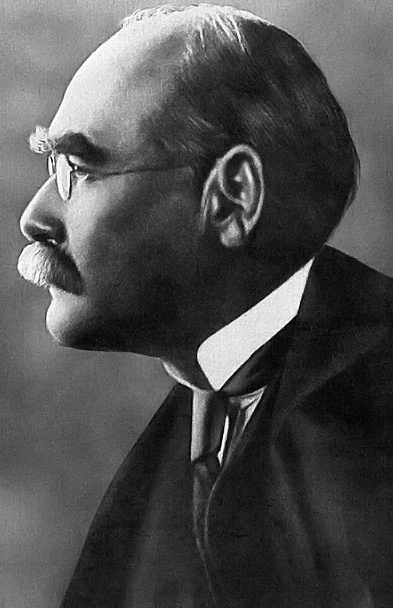

The British writer, Rudyard Kipling, who was born in India in 1856 and died in England in 1936, was the first English-language writer to win the Nobel Prize for Literature (1). He was a prolific writer whose subjects ranged from “An Almanac of Twelve Sports” to “The Man Who Would be King”, (which was made into a movie). He is best known for his works of fiction, particularly those written for children, such as The Jungle Book collection, later popularized by Walt Disney.

Kipling was buried in “Poet’s Corner” (2) , Westminster Abbey, London, together with other British literary icons, such as Chaucer, Dickens and Thomas Macaulay.

Despite his distinguished literary career, Kipling was criticized by those who saw him as a militarist and a jingoist. George Orwell called him “the prophet of British imperialism.” Virginia Woolf wrote of him: “It is true that Mr Kipling shouts, 'Hurrah for the Empire!' and puts out his tongue at her enemies".

As part of Kipling’s literary legacy, he is remembered for his stirring poem, IF, translated into many languages. Here is the poem, with a French version by André Maurois (3).

If you can keep your head when all about you

Are losing theirs and blaming it on you;

If you can trust yourself when all men doubt you,

But make allowance for their doubting too;

If you can wait and not be tired by waiting,

Or, being lied about, don't deal in lies,

Or, being hated, don't give way to hating,

And yet don't look too good, nor talk too wise;

If you can dream - and not make dreams your master;

If you can think - and not make thoughts your aim;

If you can meet with triumph and disaster

And treat those two imposters just the same;

If you can bear to hear the truth you've spoken

Twisted by knaves to make a trap for fools,

Or watch the things you gave your life to broken,

And stoop and build 'em up with worn-out tools;

If you can make one heap of all your winnings

And risk it on one turn of pitch-and-toss,

And lose, and start again at your beginnings

And never breath a word about your loss;

If you can force your heart and nerve and sinew

To serve your turn long after they are gone,

And so hold on when there is nothing in you

Except the Will which says to them: "Hold on";

If you can talk with crowds and keep your virtue,

Or walk with kings - nor lose the common touch;

If neither foes nor loving friends can hurt you;

If all men count with you, but none too much;

If you can fill the unforgiving minute

With sixty seconds' worth of distance run -

Yours is the Earth and everything that's in it,

And - which is more - you'll be a Man my son!

Si tu peux voir détruit l'ouvrage de ta vie

Et sans dire un seul mot te mettre à rebâtir,

Ou perdre en un seul coup le gain de cent parties

Sans un geste et sans un soupir ;

Si tu peux être amant sans être fou d'amour,

Si tu peux être fort sans cesser d'être tendre,

Et, te sentant haï, sans haïr à ton tour,

Pourtant lutter et te défendre ;

Si tu peux supporter d'entendre tes paroles

Travesties par des gueux pour exciter des sots,

Et d'entendre mentir sur toi leurs bouches folles

Sans mentir toi-même d'un mot ;

Si tu peux rester digne en étant populaire,

Si tu peux rester peuple en conseillant les rois,

Et si tu peux aimer tous tes amis en frère,

Sans qu'aucun d'eux soit tout pour toi ;

Si tu sais méditer, observer et connaître,

Sans jamais devenir sceptique ou destructeur,

Rêver, mais sans laisser ton rêve être ton maître,

Penser sans n'être qu'un penseur ;

Si tu peux être dur sans jamais être en rage,

Si tu peux être brave et jamais imprudent,

Si tu sais être bon, si tu sais être sage,

Sans être moral ni pédant ;

Si tu peux rencontrer Triomphe après Défaite

Et recevoir ces deux menteurs d'un même front,

Si tu peux conserver ton courage et ta tête

Quand tous les autres les perdront,

Alors les Rois, les Dieux, la Chance et la Victoire

Seront à tous jamais tes esclaves soumis,

Et, ce qui vaut mieux que les Rois et la Gloire

Tu seras un homme, mon fils.

It should be noted that the above French version is not a translation, as we normally understand that term. Parts of the English version have been translated into French but other parts have been rendered very freely to convey the spirit of the poem.

Rudyard Kipling (1865-1936)

http://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rudyard_Kipling

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=l1Ky6I3Scjw

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4Li3LPgjWcI&feature=related

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=is-JCJCUy18&feature=related

Chanté par Bernard Lavilliers

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=E1gDoZpl7Fk

Source: http://ebooks.adelaide.edu.au/k/kipling/rudyard/

(1) http://nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/literature/laureates

(2) http://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Coin_des_po%C3%A8tes

(3) http://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Andre_Maurois

Bonjour René et Jonathan,

RépondreSupprimerL'adaptation d'André Maurois est évidemment très libre, trop, même, pour qu'il vaille la peine d'en faire une critique serrée du point de vue de la traduction.

La critique pourrait être dure même du point de vue de l'écriture. Par exemple, les idées respectives des deux premiers vers devraient être interverties: le poème français commence par l'idée négative («Si tu peux voir détruit...») et c'est celle-là que retiendra le lecteur, à mon avis (s'il se rend jusqu'à la fin, avec ce boulet à traîner...).

L'anglais commence par l'idée positive très forte «If you can keep your head...», et il reste à l'auteur à tenir ses promesses. À chacun de juger s'il les tient.

Humble avis, et très cordiales salutations. Yves

Je dirais qu'il s'agit d'une véritable «personnalisation», ce qui va plus loin qu'une adaptation. Je n'ai rien contre, c'est même original. La grande originalité ici a consisté à changer complètement l'ordre des lignes.

RépondreSupprimer*Cependant*, il y a des pertes énormes. Par exemple, les vers 27 et 28 du français qui correspondent aux vers 1 et 2 de l'original.

Je me suis offert une version de Summertime de Heyward/Gershwin il y a quelque temps (http://termexplore.wordpress.com/2009/01/09/soleil-brille-summertime/), où, après beaucoup de réflexion, j'ai laissé tomber le mot «cotton», pourtant central dans l'iconographie du Sud. J'ai utilisé le mot récolte, qui me semble porter une charge semblable, au lieu du mot coton qui a plusieurs connotations propres au français, et même propres au québécois, tout à fait éloignées. Je crois que ce n'est pas une personnalisation, et que la «perte» traductionnelle est compensée.